Notable Disclosure Excerpts and Errors from Judges Heading Toward Senior Status

The Ethics in Government Act of 1978 requires that federal judges and Supreme Court justices to file annual financial disclosure reports. The purpose of these reports, according to the Guide to Judiciary Policy, Vol. 2, Pt. D, is “to ensure confidence in the integrity of the federal government by demonstrating that they are able to carry out their duties without compromising the public trust.”

These forms are designed to reveal information “relevant to the administration and application of conflict of interest laws, statutes on ethical conduct or financial interests, and regulations on standards of ethical conduct.” Neglectful mistakes and inconsistent redactions by judges undermine the clear purpose of the disclosure process and should not be tolerated by the AO—but they are.

Neglectful mistakes

Judges often serve for years either without knowing the rules or without attentively completing their financial disclosures.

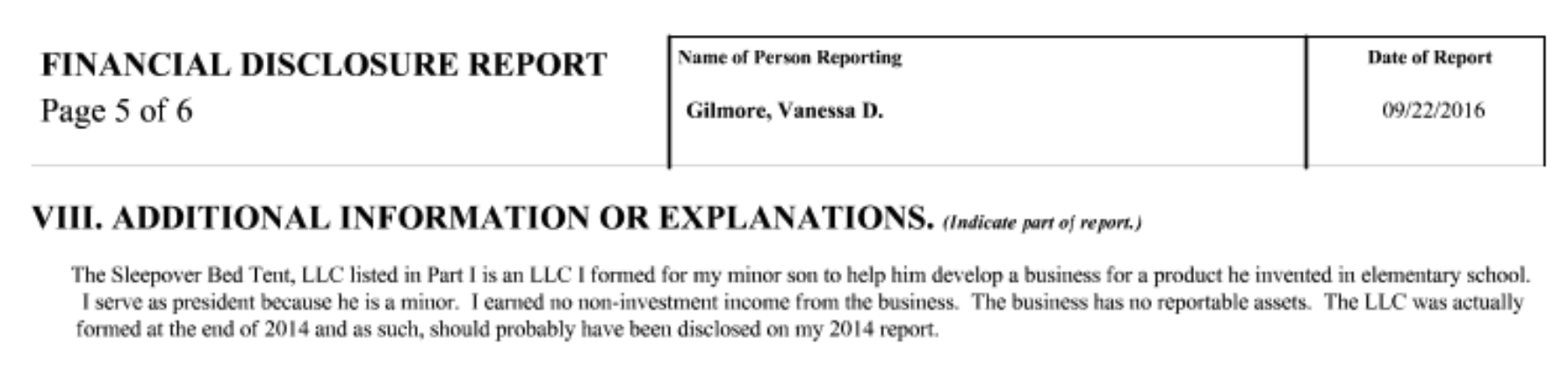

Judge Gilmore (S.D. Tex.) noted, a year late, that an LLC she formed ”should probably have been disclosed” the year prior.

Three financial holdings of Judge Alsup (N.D. Calif.) went undisclosed in 2017 (see 2018, section VIII) because, in his words, “through error on my part I failed to realize it.”

Judge Viken (D. S.D.) recently (2017) learned that certain investments “were reportable.”

It took Judge Blake (D. Md.) a few years to discover she should report serving as Vice President of her court’s historical society nonprofit and a year to learn that certain pensions must also be reported (both 2014).

In 2013 Judge Hollander (D. Md.) disclosed she “inadvertently neglected to include it [a checking and savings account] in the prior year.”

Judge Chin (Second Circuit) “inadvertently neglected to include” that he had been a member of the Board of Trustees of Princeton for two years, before realizing his mistake in 2015.

Inconsistent redactions

The Committee on Financial Disclosure and/or the U.S. Marshals Service decided that Judge Katzmann (Second Circuit) should start redacting the fact that he’s a director at The Governance Institute and a lecturer at the NYU School of Law (cf., 2012 to 2013).

Redacting sensitive information is a legitimate practice, but also one rife for abuse—to his credit, Judge Chin recently began to stop redacting the word “spouse” (see 2017 to 2018); as did Judge Viken (see 2014 to 2015) after having previously flirted with leaving “spouse” unredacted in 2011.

Similarly, Judge Winmill (D. Ida.) has learned (see 2011 to 2012) that there’s no legitimate privacy risk to noting the general physical location of a bank which holds an account of his.

Conclusion

While mistakes are inevitable, it is troubling that the system as it exists allows some of them to go uncaught and uncorrected for a full year or even years on end.

We highlight these mistakes not for their uniqueness, but for their relative banality—that this study only comprised a handful of judges across a handful of years suggests strongly that more mistakes are being made with no strong mechanism in place to catch and correct them in a timely fashion.

That this is tolerated invites additional statutory requirements to ensure the public has access to the information required to fairly assess its judicial officers nonjudicial interests.