Fix the Court's OT20 SCOTUS Recusal Summary

By Tyler Cooper, FTC senior researcher

While OT20 was arguably the most open term at the Supreme Court to date — COVID forced virtual arguments, which compelled the court to provide live online access of argument audio — SCOTUS still declined Fix the Court’s longstanding invitation to provide brief explanations for times when a justice is forced to disqualify himself or herself from participation in a case, and so, once again, FTC has stepped up to fill in the gaps.

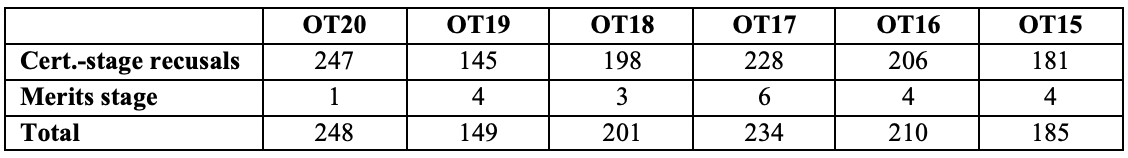

Here’s how OT20 compares to what we’ve found in our previous reports:

The spike in OT20 recusals was driven primarily by three factors:

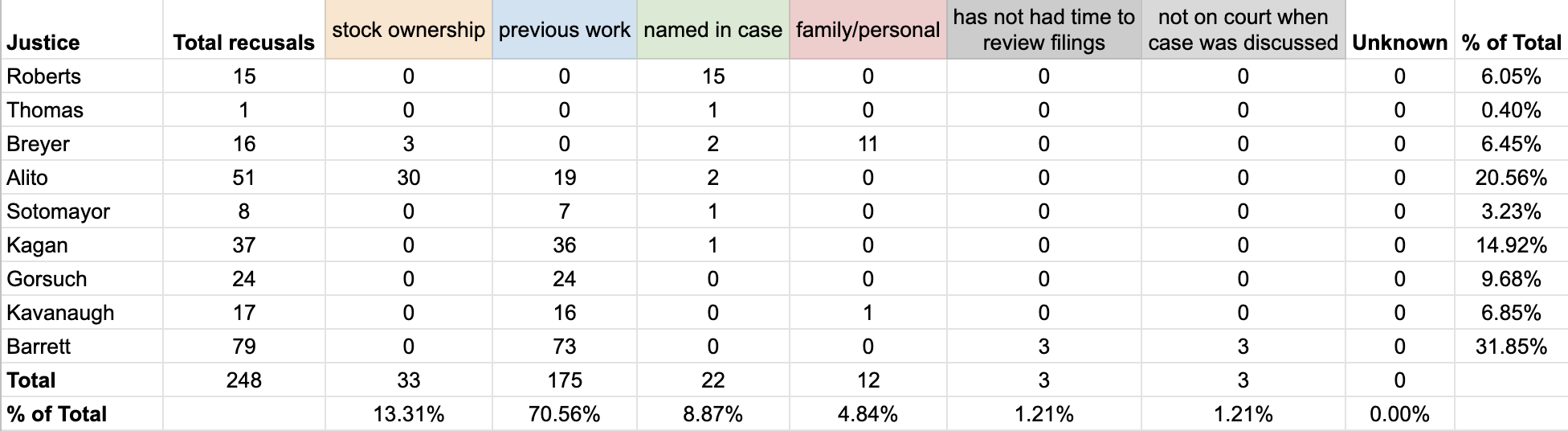

1) A new justice was added to the bench. Justice Amy Coney Barrett was sworn in on Oct. 27, 2020, and all told, she logged 79 recusals last term, leading all justices. That’s to be expected.

What’s interesting here is that court was uncharacteristically more forthcoming about a handful of these: three of them were recusals from shadow docket orders that the public information office, via SCOTUSblog, said Barrett was disqualified from because she “had not yet had an opportunity to fully review the filings in the case.” In addition, three more recusals came from per curiam orders issued on Nov. 2, which we presume were drafted prior to Barrett’s joining the court. For these we created two new recusal categories: “has not had time to review filings” and “not on court when case was discussed,” respectively.

2) Alito continued to prioritize his financial portfolio over his public duties. Only three justices insist on holding individual stock, but of the three, only Justice Sam Alito allowed his holdings to routinely force his disqualification in OT20. Of the 51 times Alito recused in OT20, 30 were due to his stock holdings. The other two stock-owning justices (Chief Justice John Roberts and Justice Stephen Breyer) were forced to disqualify due to their financial interests only three times in OT20. SCOTUS stock ownership forced recusal 16 times in OT19, 13 times in OT18, 45 times in OT17, and 47 times in OT16.

3) Bad luck. Being named in a case or having a family or personal conflict requires disqualification, and — unlike stock holdings — aren’t conflicts a justice can prevent. A total 34 recusals in OT20 were due to one of these two categories, while only 16 of them occurred in OT19, 17 in OT18, 18 in OT17 and 24 in OT16.

The one merits-stage recusal came from Alito (stock ownership) in 19-1189, BP P.L.C., et al., v. Mayor and City Council of Baltimore. He owns up to $50,000 in shares in two parties, ConocoPhillips and Phillip66.

This very case was also notable for a non-recusal. Shell was also party to it. And you may recall that Barrett included a litany of Shell entities on her conflicts sheet in Sept. 2020 and yet apparently did not consider her father’s 30-year employment with Shell to demand her disqualification in Jan. 2021. At the time we suggested this may be because SCOTUS justices often construe conflicts more narrowly since they’re not fungible the way appellate judges are. Regardless, we’d all be better served if the justice herself shared her thinking here.

Relatedly, if and when a litigant donates, say, $1 million to support your elevation, you should probably recuse when said litigant has a case come before you a mere six months after your confirmation.

Until all the justices do start sharing brief explanations alongside their recusals, or until Congress mandates that they do so, we’ll continue tracking them down and providing periodic public updates.

Here’s what we’ve got going for OT21.