The Judiciary Wants to Increase the Size of the Lower Courts. This Is How We'd Do It.

(This post was originally published in March 2019 but was updated in June 2020 prior to the SJC hearing.)

At a hearing next week, the Senate will examine the Judicial Conference’s biennial recommendation on adding new Article III judgeships. The question you may have is how would Congress add judges in a way that doesn’t lead to a political explosion?

The answer, much like with term limits, is staggering the judgeships.

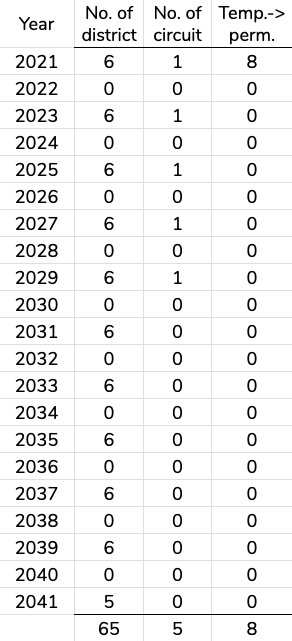

Under our plan (see chart at right), one new circuit judge and six new district judges would be added to the bench every two years, with the entire roster of new judges in place by 2041.

Federal caseloads have increased 30 percent since 1990, which was the last time Congress enacted a major bill to increase the size of the courts to keep up with filings.

This go-round, the Judicial Conference is calling for 65 new district judgeships, five new circuit judgeships and eight temporary district judgeships becoming permanent. This is an increase from the 2017 Conference list, which requested 52, five and eight, respectively.

Here’s how our plan would work:

(1) After the Judicial Conference’s spring meeting in even-numbered years, the Conference would recommend to the House and Senate Appropriations Committees which seven judgeships of the 78 outstanding (see chart at right) should be authorized in the following year’s budget based on current caseloads.

(2) The Appropriations Committees would over the next few months debate those recommendations and hopefully agree with them.

(3) Assuming they do, or even if they wanted to add seven different judgeships of their choosing, money for those judgeships would be included in the final appropriations bill, which would include language to create those judgeships in January of the following year.

(4) In other words, a spring 2020 recommendation would lead to a summer/fall 2020 appropriation and a Jan. 2021 new slate of judgeships.

(5) The eight temporary-to-permanent judgeships may be added at any point.

Two decades may seem like a long time to arrive at a fully staffed bench, but given the contentiousness of adding new judgeships, we believe it may be better to start small and go steady than try to go big and end up with nothing.

In 2018 , the House Judiciary Committee passed the Judiciary ROOM Act, which had in it the 52 new district judges and the eight temporary to permanent judges, per the JCUS recommendation. The bill as passed also included an amendment introduced by Rep. Jamie Raskin that would have delayed the start of the new judgeships to 2021, which would have meant that no one would have known who the appointing president, or the confirming senators, would be.

The major sticking point in the bill, though, was that the parties could not find agreement on how to pay for the new judgeships, which cost about $750,000 million each per year (think salaries, support staff, office space and supplies, IT needs, retirement accounts, etc.).

Though FTC’s proposal does not address the cost issue, since Congress can now come up with trillions of dollars in an instant, coming up with the $5.25 million it would cost to add these new judges doesn’t seem difficult.

Should caseloads continue to rise at a rate the outpaces the newly added judgeships, the Judicial Conference should return to Congress with updated recommendations that may yield a different formula.

Finally, it is also likely that an increase in the number of federal magistrate judges could help alleviate the caseload problem, though we do not yet have specific numbers or projections for this piece of the puzzle (cf. “The federal courts need more judges — magistrates can help,” June 20, 2018).