"Virtually All of Us Are Committed" to SCOTUS's Ethics Code, Justice Sotomayor Tells Swiss Audience in Newly Unearthed Audio

In a wide-ranging talk, the audio of which Fix the Court just found and posted, SCOTUS’s senior liberal said term limits could bring political balance to the bench — “a great value” — and owned up to missing a recusal

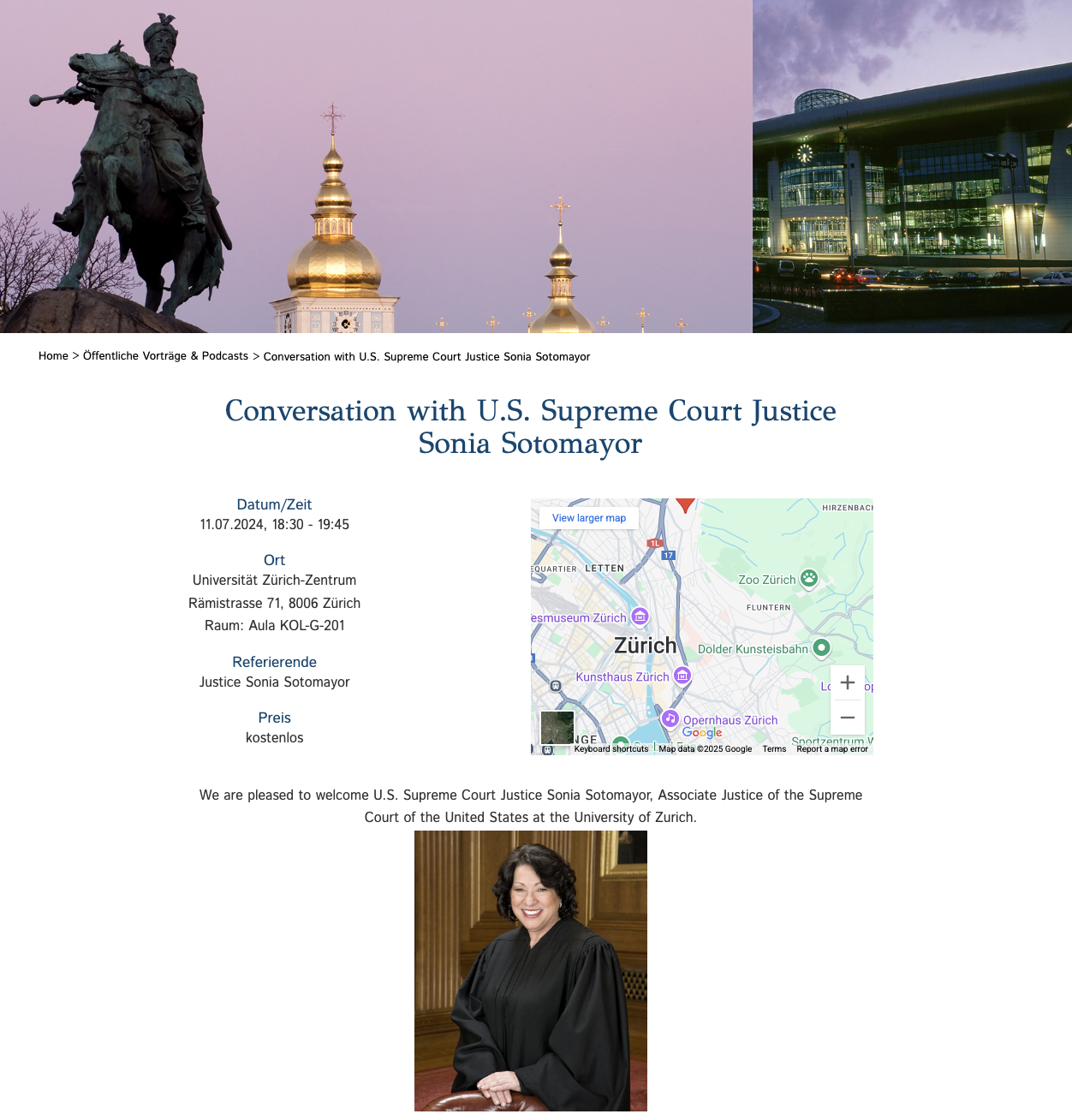

At a July 11, 2024, appearance at the University of Zurich, Justice Sotomayor offered insights on ethics codes and term limits proposals that she’s not given stateside, owning up to a “mistake” she made — first identified by Fix the Court — by not recusing in a petition and highlighting the positives for ending life tenure at SCOTUS.

In what might have been the most telling comment of the event, Sotomayor said that “virtually all of us (justices) are committed” to the Court’s new ethics code, albeit without specifying what she meant by “virtually.” Unfortunately, there was no follow up question to that comment.

Term limits would “keep the balance”

During the talk, a Q&A with Swiss scholar Andreas Kellerhals and Swiss journalist Isabelle Jacobi, the audio of which FTC’s Manny Marotta obtained last month that we’re posting here for the first time (key excerpts | full audio), Kellerhalls asked Sotomayor about the benefits and drawbacks of ending life tenure.

She said that several older justices, like John Paul Stevens, served ably into their old age, but noted that “the rest of the world tends to have functioning courts with term limits.”

Sotomayor added that term limits would end the incentive to appoint young nominees and would “keep the long-term balance” — that is, in terms of which party appointed the justices — “[from] becoming skewed for too long, [which] is a great value.”

She then poured cold water on a popular idea in some liberal circles whereby once 18-year term limits were implemented, each new justice would replace an older justice on the bench in order of their seniority. That’s what Rep. Hank Johnson’s TERM Act would do, for example.

Countered Sotomayor: “The problem with a term limit is how will they institute it, because I am promised my job for life, and that can’t be taken away constitutionally — I don’t believe even with a constitutional amendment — because you cannot have a retroactive law changing something that you’ve earned.”

Sotomayor described another option for implementation, where the current justices would serve “for as long as they want,” which is consistent with Rep. Ro Khanna’s term limits bill that FTC worked on. But she added that that proposal “might not [realize] the value of term limits” since, as she indicated, the terms of the current nine could not be abridged. (We still think it’s worth implementing; read other justices’ views on term limits here.)

Either way, she did say that term limits could be a decision “of the legislature in a vote some day,” implying that the policy could be implemented via statute, as FTC has argued.

Adherence to ethics doesn’t mean no “mistakes”

When Jacobi asked about the SCOTUS code of conduct, Sotomayor said striving to act ethically “does not mean that mistakes are not made. I’ve made one. I failed to notice that there was a party of my book publisher who was in a case.”

That mistake was pre-code, and she’s made others, of course, but, as FTC’s Gabe Roth stated, “Any acknowledgement of error by a justice is a big deal.”

The case she referred to could either be Nicassio v. Viacom International, et al. (cert. denied Dec. 9, 2019; rehearing denied Feb. 24, 2020), or Whitehead v. Netflix, et al. (cert. denied May 17, 2021), as in both, Penguin Random House was a party on the respondents’ (“et al.”) side.

In various reports and press outreach, FTC identified these errors when they happened and has maintained that, as a rule, the justices should recuse in cases and petitions involving their book publishers, which pay them handsomely. (Sotomayor alone has earned nearly $4 million in royalties and advances.)

Recusals finally happened this past May, as the four justices who have contracts with Penguin Random House, including Sotomayor, stepped aside in a petition in which Penguin was a respondent.

Finally on ethics, Sotomayor said that “no matter what code we write, […] it’s unenforceable on its own” because “constitutionally the only entity who can enforce it is Congress.”

She added: “So we are relying on the good will of each of us individually to honor the code that we’ve signed onto, that I believe that virtually all of us are committed to.”

Though she emphasized that impeachment will always be the primary ethics enforcement mechanism, she did not rule out other sanctions or guardrails that could one day be imposed by Congress.

Below is the transcript of the two answers referenced above. The first timestamp is from our edit of the audio and the second is from the larger file available here:

Europa Institut Director Andreas Kellerhals (0:00/47:30): Justices of the U.S. Supreme Court are appointed for life, and you and only you basically decide when you want to stop doing that. Is this a good system, or is this making the justices too powerful?

Sotomayor: You know, this is a question that my community, the American community, is now looking at. And I’m always hesitant to express my personal views because when people ask me about that in America, my answer is, what do you think? Same answer. Because it’s really what the populace is going to conclude, what our country in a vote some day, or the legislature in a vote some day, is going to determine is important for us. I can point out how the question exists on both sides of that.

With respect to life tenure, I think we may be the only country in the world that has life tenure for its federal judges. If there’s some other country, I don’t know it, or don’t remember it. But most of the world, including Switzerland and most European countries, have term limits of some sort or another.

On that side of life appointment is the value that experience brings to a job, and what’s the right number of years for a term, alright? We have had some very senior justices who have probably been on the court longer than they should have been [Kellerhals: No names, right?], but we have had some justices, like John Paul Stevens, who served on the court until he was 90 years old.

And I can share with you that I know why he stepped down. And it wasn’t because he had lost any mental acuity. It was because he knew that the time had come not to take the risk. But up until the moment he resigned, our court would have been the lesser if he [had] not been there.

And so how do we create a system, and at what point do you say, should you stop serving? When does the value stop growing? I’ve been a justice for now, I think I’m going into my 16th year. I’ve been a judge for 30-plus [years]. I hope I’m still growing, and I think I am, and I hope I will. When I no longer feel that I’m making incrementally or writing incrementally better decisions, I will quit. And we rely on that good faith of the justices if life tenure continues to be the mode. […]

I worry, too, with [life] tenure, that there is a drive to appoint younger people rather than older people to be judges, and I know that among you, there are people in their 70s — myself included; I’m 70 this month — there are people in their 80s or are 85 who are brilliant. And once you have a [life] tenure system, the impetus is not to appoint older people. And you lose the value that experience brings, alright?

On the other side of the equation, term limits. Everyone else seems to have survived very well with them. The rest of the world tends to have functioning courts with term limits. It removes some of the political chance of life tenure because then it’s tied to the society, meaning, a judge steps down, and it’s the political party who’s in power that will make that appointment, but if the people are unhappy with that, you’ll have a different party, and you’ll have a different appointment in a certain number of years. And that will keep the long-term balance [from] becoming skewed for too long. So that is a great value.

In the American system, the problem with a term limit is how will they institute it, because I am promised my job for life, and that can’t be taken away constitutionally — I don’t believe even with a constitutional amendment — because you cannot have a retroactive law changing something that you’ve earned.

So that means that a current court at the moment these term limits exist, those justices will be there for as long as they want, so you might not get the value of term limits in the United States because of that inherent difficulty.

So I have my own personal view, but I do think it’s an issue that Americans have to think about very closely.

Neue Zürcher Zeitung reporter Isabelle Jacobi (6:14/53:44): How important is this [new] code of conduct, first of all, and can there be too much accountability?

Sotomayor: There can’t ever be too much accountability. [Applause.] But I think that you have to sit back, as we all do, to realize that codes of conduct are words on paper. Laws are words on paper. People break them every day. And people break laws and get away with it every day. And people break laws and maybe not get away with them but still pay the price because that’s the choice they’re making. Rules depend, not on laws or codes of conduct, rules depend on your personal senses of integrity. That is what keeps us functioning as a society. That’s what keeps people honest. […]

For judges of the Supreme Court, for federal judges generally, the only check on us constitutionally is impeachment. We have had lower court federal judges who have committed crimes, been convicted and have refused to leave office, and they have had to be impeached by Congress. So no matter what code we write as justices [it] is unenforceable on its own. It’s unenforceable because constitutionally the only entity who can enforce it is Congress. So we are relying on the good will of each of us individually to honor the code that we’ve signed onto, that I believe that virtually all of us are committed to.

It does not mean that mistakes are not made. I’ve made one. I failed to notice that there was a party of my book publisher who was in a case. It’s a long story but my staff was checking one document for conflicts, and it wasn’t a full document of all the parties, and so it got missed.

Now I didn’t even realize that they were a party, so I didn’t vote believing I was favoring my publisher. But the point is that’s a mistake. And I’m sure that some of the things that you have read about that were not reported were also due to mistakes — maybe not all, but I don’t know — but I’m sure many were.

So the point that’s in answer to your question is every law depends on the good will of the people who have to live by it. But that’s true of every member of society. And that’s true of every single profession in society. And that’s why the integrity of the people you appoint is important. It’s a factor that has to be considered, and it is a factor in every judgment you make in life about what you’re doing or choosing not to do.