Chief Judges Shouldn't Review JCDA Complaints Filed By People Who Just Had a Case Before Them

Say someone, anyone, files with the chief judge of a circuit a formal complaint against a district court judge.

Say someone, anyone, files with the chief judge of a circuit a formal complaint against a district court judge.

This complainant raises some interesting points so instead of dismissing it outright (more than 90 percent of JCDA complaints are frivolous or out of order), the chief judge writes out a several-page order acknowledging the points but explaining why, under the rules, he must dismiss it.

Then say the complaint arose from a court case for which the same chief judge sat on a three-judge panel less than a year prior. Shouldn’t there be a rule that requires or suggests recusal given the temporal proximity?

Here are the facts more directly: a Florida man, Clyde Dandridge, took issue with a mediator assigned to his discrimination case against Wal-Mart. Earlier in her career, the mediator had worked at a law firm that had represented Wal-Mart, and Dandridge thought there may be a conflict so tried to get a new mediator. (He failed.)

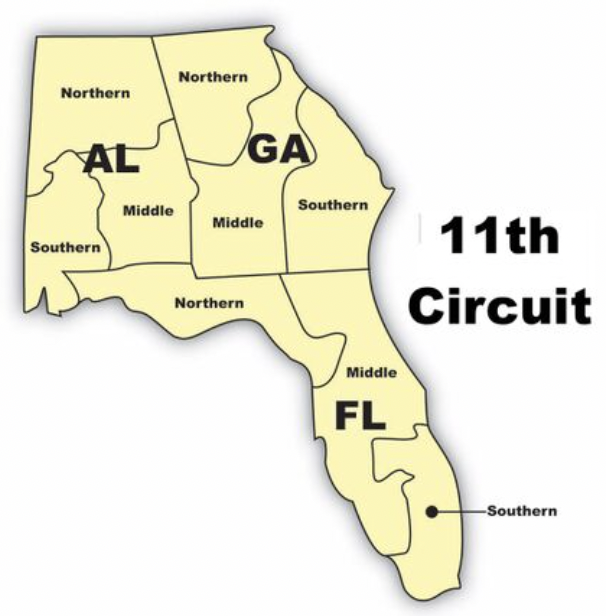

Dandridge lost and appealed his case to the Eleventh Circuit. Chief Judge Bill Pryor sat on the panel that twice dismissed his.

After a little while, Dandridge filed with Pryor a complaint against the district court judge who had made the mediator assignment.

Dandridge raised several thoughtful, though ultimately not relevant, points in his complaint, including one where he maintained that the judge’s ownership of stocks of certain large funds and financial institutions that are major Wal-Mart shareholders required his recusal from Dandridge’s case. (It didn’t; ownership of shares in a mutual fund rarely if ever triggers recusal, but it’s easy to understand why someone would think it might.)

Pryor, to his credit, spent a dozen pages in an order walking through the complaint and explaining why he would have to dismiss it under federal law and the Rules for Judicial-Conduct and Judicial-Disability Proceedings. (Frankly, we wish more chief judges were as comprehensive in their analyses of complaints, even when, like Dandridge’s, they ultimately fail.)

A problem potentially arises with Pryor not only adjudicating the complaint (May 2022) but also having adjudicated Dandridge’s case in 2021.

Again, no one did anything wrong here, but one could imagine a scenario where a chief judge rules against a litigant one day and has to review a complaint (about that case, about something else — doesn’t matter) from the litigant the next day.

There’s some inherent or potential bias baked in to that scenario.

So in order to alleviate the appearances issue, it might be better, then, to require chief judges to recuse from complaints filed by individuals who had cases before them in, say, the prior two or three years.

Fix the Court has raised this issue to the chair of the Judicial Conference’s Committee on Judicial Conduct and Disability, and we’ll let you know if they offer a response.