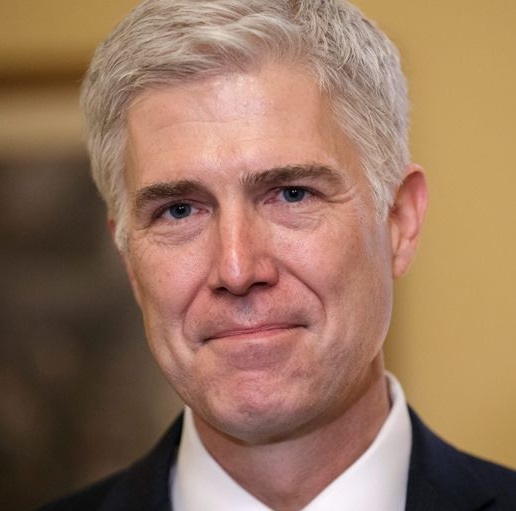

Justice Gorsuch's Recusal Is the Correct (Albeit Belated) Call

By Kit Beyer, FTC law clerk

On Dec. 10, the Supreme Court will hear argument in Seven County Infrastructure Coalition v. Eagle County, Colo. — sans Justice Gorsuch, whose former client in private practice, billionaire Philip Anschutz, stands to benefit from the Court’s ruling.

On Dec. 10, the Supreme Court will hear argument in Seven County Infrastructure Coalition v. Eagle County, Colo. — sans Justice Gorsuch, whose former client in private practice, billionaire Philip Anschutz, stands to benefit from the Court’s ruling.

Anschutz heads the eponymous Anschutz Exploration Corporation, an oil and gas company that filed a brief in the case urging the Court to constrict the scope of the National Environmental Policy Act’s environmental review requirements.

Gorsuch’s voluntary disqualification, announced in a statement from the clerk of the Supreme Court on Dec. 4, comes after a dozen lawmakers sent him a letter urging recusal due to “a serious and obvious conflict of interest,” citing the Supreme Court’s recently adopted, self-enforcing Code of Conduct.

Previously, watchdog group Accountable.US had sent a similar letter to Chief Justice Roberts calling for Gorsuch to recuse owing to his “cozy relationship” with Anschutz.

It’s ultimately unclear, however, what prompted Gorsuch to recuse just days before the oral argument.

The announcement, comprising just 40 words, points to the Code of Conduct, which is, of course, non-binding.

While serving as a judge on the Tenth Circuit, then-Judge Gorsuch routinely recused himself from cases involving Anschutz. By contrast, after his nomination to the Supreme Court, when reporting from the New York Times raised the possibility of future conflicts of interests, he made no public recusal commitment.

It’s possible the pressure from Congress persuaded Gorsuch to recuse when he had previously intended to continue participating in the case. Alternatively, he may have made the choice out of genuine concern that his impartiality “might reasonably be questioned,” the Code’s and the federal recusal statute’s standard for recusal.

Whatever the case, it’s a welcome development.

It’s regrettable, though, that decisions as important as whether to recuse, affecting fundamental questions of accountability, currently rest on each individual justice’s private discretion.

Until and unless the Court has an enforceable ethics regime, the justices remain accountable only to themselves. Indeed, as the Court debated the adoption of its Code, Gorsuch vocally defended this status quo, opposing potential enforcement mechanisms, such as a proposal by his colleague Justice Kagan, as threats to judicial independence.

But seeing as states across the country impose enforceable ethics rules on their own high courts — and few would suggest that judicial independence has wilted away everywhere but One First Street — this argument falls flat.

An independent judiciary can (and should) comfortably coexist with binding recusal rules upholding basic ethical values.