Twice in One Day, Rep. Issa Asserts Congress's Legitimate Role in Legislating Judicial Ethics Standards

By Tyler Cooper, FTC senior researcher

One idea that’s taken on a prominent role in the judiciary’s congressional lobbying campaigns of late is a suggestion that any legislative efforts on ethics and recusals should be a considered constitutionally suspect, as they may be possible violations of the separation of powers and an infringement on the domain of the judiciary as a co-equal branch.

This is position, though, belies the long and accepted history of Congress setting standards for both the judiciary and executive branches, in addition to themselves.

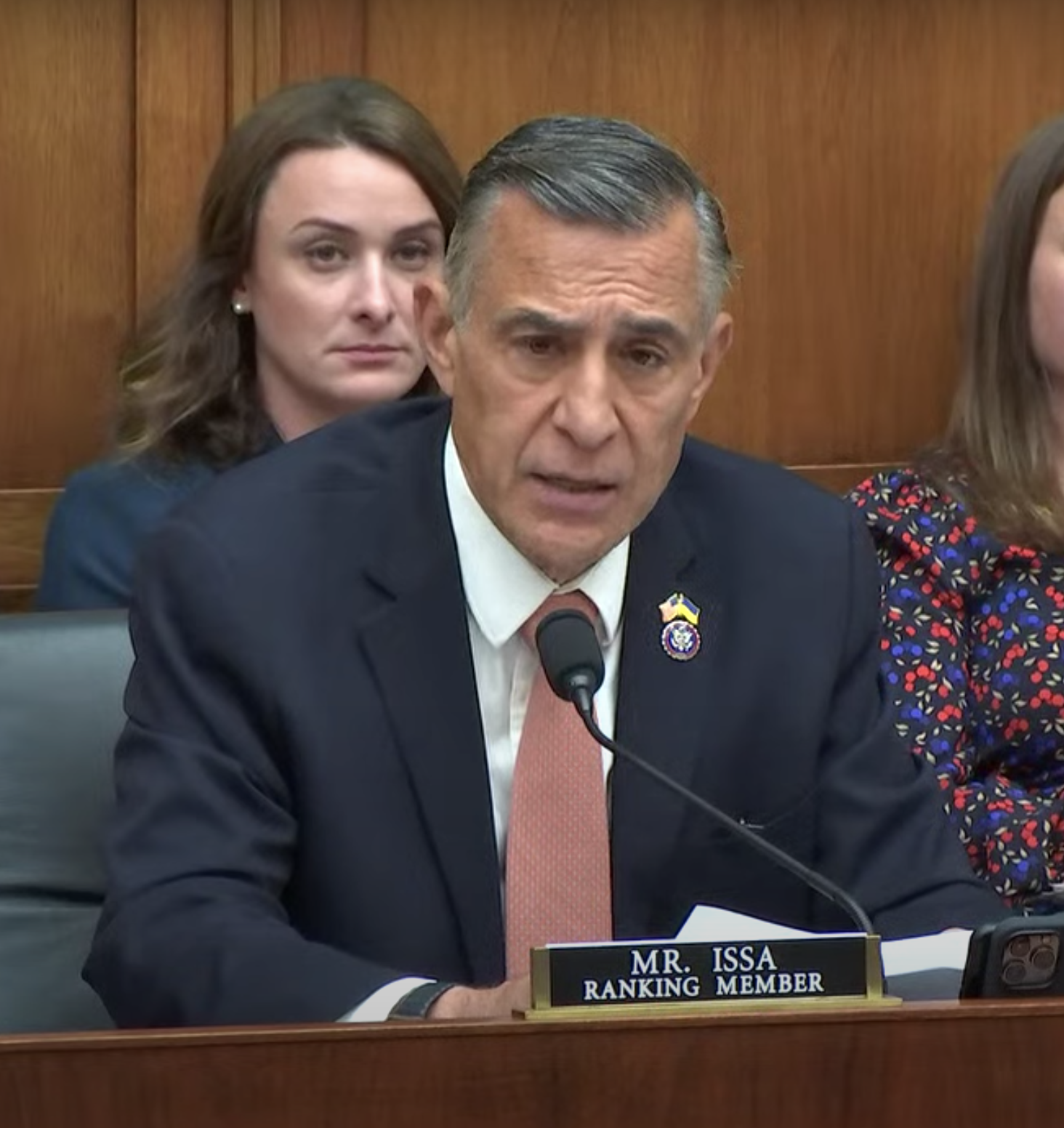

Rep. Darrell Issa of California spoke out against this notion twice on the same day last week, April 27. His first comments came midday on the House floor right before the House approved the Senate version of the Courthouse Ethics and Transparency Act, which will subject judges and justices to comparable financial disclosure rules as members of Congress and top executive branch officials already face.

This bill became necessary after the Wall Street Journal reported that in recent years 131 federal judge broke federal law almost 700 times by participating in cases in which they held a financial interest in a party to the case.

Here are Rep. Issa’s remarks in relevant part:

“[B]ecause there has been fairly public pushback from some members of the Article III court that we are meddling in their business, I have given it a lot of thought and discussed it with a number of scholars.

“I think the American people need to understand that the executive branch does not have the authority to pass laws, and the judicial branch does not have the ability to pass laws. When it comes to establishing laws for transparency reporting and the American people’s right to know, there is, in fact, only one body that can initiate and send for the President’s signature statutes of transparency and accountability.

“So even though this is a 1978 law being modified, the fact that there is pushback from a branch saying that under separation of powers we are somehow meddling by substantially harmonizing what the executive branch and this branch do to make sure the American people have confidence in what we own that might, in fact, be influencing what we do. It seems to be one of those areas in which I believe the American people, properly explained, would fully support.

“For that reason, I would hope that as this bill becomes law that the members of the court would recognize we had no choice. Faced with clear examples — even one being too much — of a judge who had holdings and simultaneously affected the value of those holdings while either owning them or trading them or both, we had no choice but to recognize that that absence of transparency was critical.”

Issa also spoke on this topic later that afternoon at the “Building Confidence in the Supreme Court Through Ethics and Recusal Reforms” hearing of the House Judiciary’s Courts Subcommittee, where he added the following:

“The Supreme Court does not and cannot make laws, the executive branch is not empowered to make laws, [but] we are empowered with that. Therefore, the question of whether or not mandates under law shall be placed on the other two bodies will always be determined by this body. A voluntary standard by the executive branch can be changed by the executive branch, a voluntary standard by the judicial branch can be changed by them. Only a law passed by this body, signed by the president, is binding on all of us in perpetuity or until change by similar statute.”

While the executive surely has exclusive prerogative over certain areas and certain decisions, it is very rarely suggested that Congress has no role in passing reforms which would compel the executive to abide by certain basic ethics standards.

And furthermore, when Congress has passed ethics laws on the executive, there has been no serious suggestion that doing so had undermined the necessary independent functioning of the executive branch as a co-equal branch of government.

Assuring the American people have the ability to determine that their judges are not violating federal law — as many have been caught doing very recently — through their financial holdings does nothing to undermine judicial independence. And suggesting otherwise undermines the very seriousness with which we all ought to treat the concept of judicial independence.

The judiciary does a disservice to itself and to the broader public by invoking the concept for frivolous arguments against congressional action.