Is There a "Good Reason" for Justices' Papers Not to Be Made Public? No.

By Tyler Cooper, FTC senior researcher

Who has a right to access the papers of former Supreme Court justices?

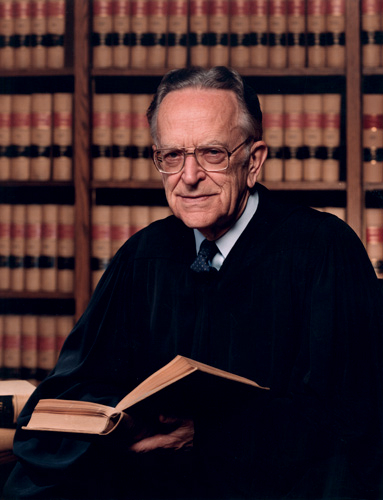

This age-old question is being asked again in light of Chief Justice Roberts citing the papers of former Justice Harry Blackmun (right) during oral arguments in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health, 19-1392. Roberts asked lawyers on both sides about the viability demarcation of fetuses, a subject that appears in Blackmun’s writings, which became public in 2004, 10 years after his retirement.

The Chief appeared conflicted on whether the papers were worth discussing — he interrupted his own question to add that he believed the very fact that he was able to premise this question on this source was “a good reason not to have [justices’] papers [made publicly available]” in the first place. (See transcript at pp. 19, 68.) Come on, Chief.

Unlike the papers of presidents, whose records are retained and later made available for dissemination under the President Records Act, the papers of justices are not governed whatsoever by federal statute. We hope to change that.

In that absence it has been left to each individual justice to determine what becomes of their papers, and justices have come up with a variety of different decisions based on their own individual whims.

The overarching theme: delay their release so long as to drastically reduce their value to contemporaneous citizens and historians.

What might be worse is that each of the seven justices whose service has ended since 2000 chose to make their papers public in a completely different way from one another.

There has not even been complete uniformity as to what materials exactly count as the “papers” of a justice.

William Rehnquist’s family donated his papers to Stanford’s Hoover Institution Archives. His first batch of papers opened up to researchers three years after his death, with all papers being restricted until the colleagues he served with at the time pass away.

Sandra Day O’Connor has her papers in an openly accessible online digital library maintained by the Sandra Day O’Connor Institute For American Democracy.

David Souter donated his personal and professional papers to the New Hampshire Historical Society, however he has required that they remain completely inaccessible until fifty years after his death.

John Paul Stevens supplied his papers to the Library of Congress, where those up to 2005 were to be opened and “freely available” by Oct. 2020. (COVID complicated what “freely available” has meant in practice.)

Antonin Scalia’s family donated his papers to Harvard Law School, with the instruction to begin making them available in 2020, with the caveat that papers related to specific cases be kept sealed until the other ruling justices passing.

Neither Anthony Kennedy nor Ruth Bader Ginsburg provided complete clarity to the public as to how their papers would be made available. (A justice-by-justice description follows at the end of this post.)

That these decisions have been made on an ad hoc basis by the individual justice belies the fact that Supreme Court justices are public servants and their work products are therefore public records.

Congress should write a statute akin to the Presidential Records Act to reflect this reality.

———————————————————————————————————————————————-

William Rehnquist, service terminated 2005

- Donated by the family to the Hoover Institution (Stanford) Archives (link)

- The papers from the 1972 and 1973 Supreme Court terms were opened to researchers in 2008. Papers from the 1974 Supreme Court term and Rehnquist’s correspondence files from 1972 through 2005 were opened by 2009 (link)

- The papers are set to be restricted on a rolling basis, opening up when the colleagues with whom Rehnquist served die (link)

- The collection included case-related materials, speeches, personal correspondence, drafts and notes on the many books he authored, and in-chambers correspondence among the justices (link)

Sandra Day O’Connor, service terminated 2006

- The Sandra Day O’Connor Institute For American Democracy has an openly accessible online digital library (link)

David Souter, service terminated 2009

- Donated his personal and professional papers to the New Hampshire Historical Society, but with the caveat that they remain inaccessible to all for 50 years after his death (link)

John Paul Stevens, service terminated 2010

- Planned for most of his case files (up to 2005) to be opened and “freely available” at the Library of Congress by Oct. 2020 (link), though due to COVID, there’s a backlog in logging the papers and LOC hasn’t always been open in the intervening 15 months

- Further details of the arrangement have not been reported (link)

Antonin Scalia, service terminated 2016

- Donated by the family to Harvard Law School (link)

- The papers come primarily from Scalia’s time on the Supreme Court and the D.C. Circuit but also his earlier work in the U.S. Department of Justice and in other roles. (link)

- Papers from his years on the Supreme Court and D.C. Circuit were to be made available for study starting in 2020, while documents related to specific cases would still be withheld through the lifetimes the other ruling judges’ and justices’ who also participated in the case (link)

Anthony Kennedy, service terminated 2018

- There does not seem to have been any public announcement as to what will happen with his papers (link)

Ruth Bader Ginsburg, service terminated 2020

- A 2018 law review article that summarized the plans for the papers of justices said of Ginsburg, “Justice Ginsburg is already taking requests for materials from before her service on the federal bench. Nothing is publicly known about future access to her judicial papers other than that they will be accessible at some point.” (link)

- In Sept. 2020, former SCOTUS spokeswoman Kathy Arberg said Ginsburg “has not announced her plans for her Supreme Court papers.” (link)

- Arberg also said that Ginsburg “would never impose such a restriction [100-year delay on making the papers public].” (link)

- Fix the Court followed up on the above article in Feb. 2021 by emailing Arberg, who responded by saying that “the arrangements for Justice Ginsburg’s papers have not been announced.”

- Ginsburg’s case files are all scheduled to be housed at the Library of Congress, however the files will be closed to most researchers as long as any justice who participated in the decision of the matter is still alive. (link)