The Shadow Docket: Problems and Solutions

By Gabe Roth, FTC executive director, and Tyler Cooper, FTC senior researcher

View this as a one-pager here. View the House Judiciary subcommittee hearing on the topic here.

What is the “shadow docket”?

The shadow docket is a term coined by University of Chicago Law Prof. Will Baude in 2015 for the significant and increasing volume of orders and decisions the Court issues without full briefing and oral argument.

Why is it problematic?

The shadow docket becomes problematic when it is used by parties, or the justices themselves, to evade regular judicial process or to elide public scrutiny of a case.

The Trump administration, seeing the Supreme Court as friendly audience, sought to use the shadow docket as a means to bypass the regular judicial process and get an expedited ruling from the justices. The justices, in turn, frequently facilitated this strategy by deciding cases without a full briefing, oral argument or explanation. Though the Trump administration may be no more, the newly expanded conservative bloc may still choose to dispose of cases via the shadow docket when doing so can produce ideologically conservative outcomes while largely avoiding public scrutiny.

What are some solutions?

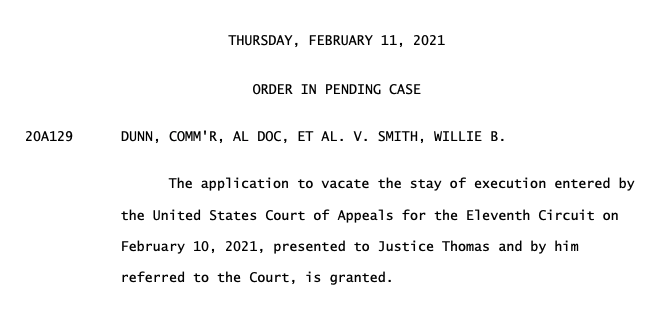

1. The Court should record how each of justice votes in each of the shadow docket cases. Sometimes, none of the justices’ votes are recorded (see right); other times, a few are left out. In any event, rendering an opinion with the imprimatur of the Supreme Court behind it shouldn’t be done without the public knowing where each justice stands.

2. Another obvious one: the justices should explain the reasoning behind their votes.

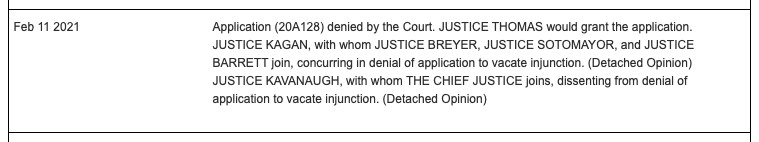

3. The Court’s homepage should have an overlay when a shadow docket opinion is handed down. Nowadays you must be an insider to know how to locate one. For example, to find a Feb. 11 death penalty ruling, one must search the SupremeCourt.gov docket for “Willie B. Smith,” a common name; figure out which of the eight hits is the right petition; and then, after scrolling through, locate a “detached opinion” (see above right) elsewhere. (Fittingly, only seven of the nine justices’ views were included in that opinion.)

4. Justices read their press, so we should praise them when they do record and explain their votes. That Justice Kagan, in the above opinion wrote “I concur in the Court’s decision […], and I write to explain why” is extraordinary, though it shouldn’t be. Contrast that with the order in the case led by Texas to overturn the 2020 election results in Pennsylvania. That came with almost no explanation, save one unsigned sentence and one half-thought.

How is the shadow docket emblematic of other transparency shortcomings at the Court?

The Supreme Court maintains a transparency deficit as compared to the other branches. Whether it’s financial disclosure obligations, live broadcast or ethics, the Court lags way behind Congress and the Executive. The recently expanded use of the shadow docket is yet another way in which the Court has demonstrated a lack of appreciation for the public’s interest in its work.

The Court’s power is derived entirely from its perceived legitimacy, and yet time and time again it’s declined to show the public that this legitimacy is deserved. Justices make less comprehensive financial disclosure statements than do officials in the other branches. The justices do not permit live video broadcast of oral argument, while Congress has long allowed C-SPAN to provide live TV-coverage of its own proceedings. Members of Congress of both chambers, as well as the President, face regular elections where their further service is subject to the will of the people, and yet judges and justices serve for life—only once being required to earn the support of the people, albeit even then only indirectly, via a majority of the Senate. Perhaps most indefensible, there is no code of ethics to which Supreme Court justices are bound. While there is a Code of Conduct for U.S. judges, the Supreme Court justices are exempt and instead are free entirely to decide ethical questions, such as recusal, entirely on their own individual whim.

It should then come as no surprise that an institution that finds even modest democratic measures of accountability anathema would also be attracted to exercising power in the shadows. To the the most powerful, least accountable branch of government what exactly is the use in an issue fully briefed, or presented in oral argument? To those on high, what’s the benefit of explaining their reasoning to the masses? When the conclusion is already written, what’s the point of additional public process? The Supreme Court surely doesn’t see any.